Listen to the episode here: carlisle-indian-school-research.zencast.website/episodes/7

So, really, the last episode went up in December? Well, that’s a pretty long hiatus but I’ll be talking in this episode about what was keeping me busy for those two months: hundreds and hundreds of images. A lot of them glass plate negatives. So come along, why don’t you, and listen to what I’ve learned from spending so much quality time with these collections.

I realized as I was struggling with this episode was that I was becoming paralyzed by trying to cover everything about the early images. That’s too much for one episode and is taking the fun out of it. So instead we’ll have a more casual discussion of some of the discoveries I’ve made.

Photograph of a photograph of the first female students upon arrival at Carlisle, October, 1879. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, NAA 74306, NAA INV 06907700.

What’s a glass plate negative anyway?

As I said in the episode, this isn’t my area. When I write an article or a book chapter on this, I’ll give a tidy summary but for now, I think it’s good enough to say it’s a piece of glass with a chemical solution on it that becomes activated by light and so produces a photographic negative. They came in different sizes, depending on what size print you wanted to make. We were—well, I was—pretty excited when the Dickinson College Archives acquired a new batch of Indian School negatives packed in these original boxes.

If you took one out of these boxes you wouldn’t see much. A plate of glass that’s mostly black with areas or gray or white. You really can’t see what’s on it. Holding it up to a light helps. Here’s what one looks like when you put it on a light table.

Better, but you still can’t tell much. But what you can see here is the handwritten caption. This one is very clear and legible (believe me, most of them are not this good!). Sometimes there’s a date, sometimes not. This should give you a basic idea of what we’re talking about.

Who is this guy Choate and why is he so important?

If you spend any time looking into the Carlisle Indian School photographs, you’re going to hear the name Choate right away. Here’s the short version, and I have links to more info at the end of this post. He was one of the photographers working in Carlisle when the school opened. Way back in Episode Six when I talked about the city directories I think I noted that there were three photographers listed in 1877-1878 and J.N. Choate at 21 West Main was one one of them. For whatever reason, Choate ended up being the most prolific local photographer associated with the school. Lots more to say about this in the future.

So what are most of the photos?

The overwhelming majority of the photos I’ve seen—and I’ve seen hundreds now, maybe into the thousands—are of students after their arrival, in uniforms, school-issued clothing, or clothing they bought for themselves in the town of Carlisle. But in this episode we’re going to focus on the oddities and discoveries.

Choate made copies of prints of his own photographs

As demonstrated by the image at the top of this post, in which the hand of the photographer, or his assistant, is visible. Presumably he did this because he broke the negatives or couldn’t find them.

Photograph of a photograph of students working in the print shop. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, NAA 73243, NAA INV 06801900.

Among the discoveries with the greatest potential impact is that Choate also took photographs of images already mounted in albums, specifically he took photos of images mounted in the so-called Indian School albums now owned by the Cumberland County Historical Society. Here are some examples—note the distinctive handwritten captions.

Five Arapaho Chiefs with Interpreter, c.1885. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution NAA 74261, NAA INV 06903200. This is a photograph of Indian School Album 1, page 36.

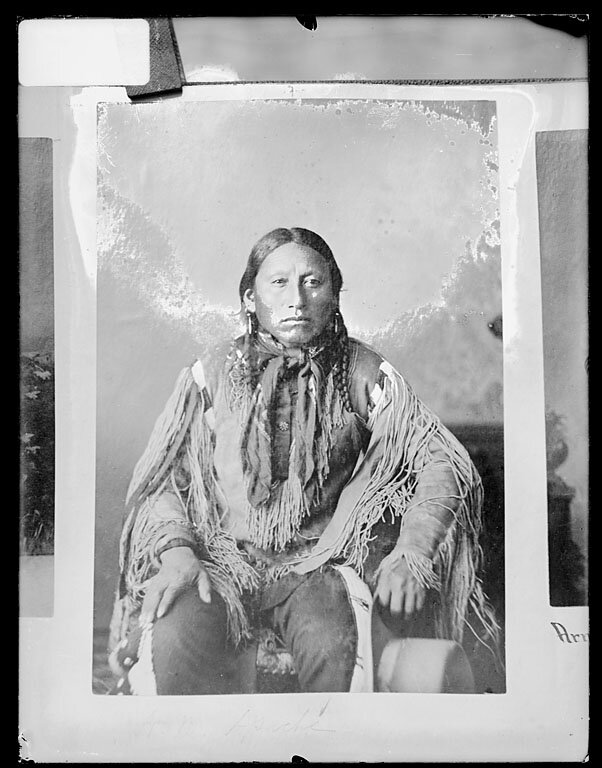

Apache Chief, c.1880. National Anthropological Archives NAA 74302; NAA INV 06907300.

And below you can see the page in the album with the images on either sides and the snippet of caption matching what shows in the negative of the copy.

Indian School Album 1, page 93 (PA-CH1-093a-c), Cumberland County Historical Society.

This opens up a host of questions—none of which I think we’ll ever be able to answer—about these albums. I believe the only information we have about them comes from a letter from Nana Pratt Hawkins in a letter to the President of what would become the Cumberland County Historical Society. She wrote:

When the Indian School was closed Mrs. Denny sent my Father, General Pratt, the School albums that were in Miss Ely’s office for the purpose of ordering duplicate prints.

Nana Pratt Hawkins to Samuel M. Goodyear, July 12, 1935.

Interestingly, her list in this letter specifies “two large albums,” While today the albums are unbound, they are cataloged as three, not two, albums.

In any case, we now know that the albums were either kept by Choate in his studio at first—and so were available to him to make copies from—or were kept at the school but borrowed by Choate when he needed them. Who wrote the captions? Who decided which photos were included? Not all of them are.

Another observation we can make—well, I can—about the photos that Choate copied is that most of them are of visiting Indian chiefs. Such photos were probably popular sellers for Choate, who marketed and sold copies of the photos he took of the students, school grounds, and visitors. The first list of Choate photos for sale includes 32 images of visiting adult Native Americans (out of a total of 89). (see “Indian Pictures!”, Eadle Keatah Toh, Vol. 1, No. 10, April 1881, page 4.)

Choate made copies of other people’s photographs

Oh yes he did, and with no credit given either, it seems. And the subjects of all the ones I’ve found so far are Native Americans, often chiefs. Here’s one:

National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, NAA 73593, NAA INV 06836700.

This didn’t look like it was taken by Choate in his studio, so I did a reverse image search (I use tineye.com) and, indeed, here it is, in the collections of the National Archives as part of a collection of portraits of Native Americans taken by William S. Soule (catalog.archives.gov/id/518890). I haven’t seen any evidence that Choate tried to sell this work as his own, just as I’ve not found any evidence that he ever tried to pass this off as his own and sell it.

National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, NAA 7345, NAA INV 06822400.

I can’t remember if also found this with a reverse images search or just searched for the text (“Young Apache Bucks in Winter”) and found that this is from a cabinet card apparently originally taken by Andrew Miller (although who knows, he may have copied it too?) but at rate, this is not a image originally taken by Choate.

I have found one instance—and there may be others—of Choate copying and selling an image he did not take. It’s #28 on the list of 89 images references above, “Indian Pictures!,”: Ouray and his wife Chipeta, Utes. The National Anthropological Archives has two negatives of Choate’s copies. Here’s one of them.

National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, NAA 73284, NAA INV 06805902.

So, there you are: BRADY WASHINGTON, D.C.. Was that kept in when Choate sold his prints? I doubt it. This is an image taken by the famous photographer Mathew Brady when Ouray and Chipeta were visiting the nation’s capital (www.loc.gov/item/2017894685/).

But the image that may give us the most insight into how Choate viewed authorship and authenticity in his images was identified in his list of images for sale as:

The first Indian boy who applied to Capt. Pratt—Ft. Berthold, D.T., Sept. 19, 1878—for education at Hampton, Va., was called out of the medicine lodge painted and decorated as seen in the picture.

And, according to Pratt’s autobiography, Battlefield and Classroom, this seems accurate. He wrote of his first recruiting trip for Hampton in September 1878 and his visit to Fort Berthold to recruit from the Gros Ventres, Mandans, and Arikara nations:

The first name on the list was that of a young man who was in the dance house getting ready for a performance the Indians had planned to give that evening. We went to the dance house and called him out. Except for breech clout he was nude and his whole body painted black with white ornamentations, particularly on the face and upper parts of his body. (p.198)

He then goes on to describe the performance given that night, “another of the many peculiar dances and pantomimes with which the different tribes entertained themselves.”

So, whether or not the young man referenced in Pratt’s memoir looked exactly like the person in the drawing captured by the photograph, for someone in Choate’s position it was surely would have seemed close enough. The drawing itself is thought be have been made by artist George Catlin in about 1832, and depicts, according the cataloging of the copy of the Choate image held by the National Anthropological Archives, Ok-Kee-Hee-De, The Owl or Evil Spirit, with Body Paint and Buffalo Hair Breech Cloth, Dancing During the O-Kee-Pa Ceremony. (I still need to work on how the Catlin images were circulated, and so how Choate would have come across this one.)

Is Choate misrepresenting his hand in this image? It’s clearly a photograph of a drawing, and he certainly took the photograph. It depicts, more or less, what he says it does, following Pratt’s description. Looking back at the text associated with the marketing of Choate’s photographs in the school newspapers—specifically the group of 89 promoted in 1881—it doesn’t specify that Choate took the photographs, only that he is offering copies for sale. Does this imply that he was the original photographer? Certainly it does to modern readers, and maybe it also did to readers at the time. Should he have given other photographers like Brady credit for their work? Our modern practices would require it, but was this kind of reproduction common at the time? I don’t know, but it seems likely.

My job is not to comment on Choate’s ethics but to learn what I can about how to interpret the circumstances of the production of the photographs marketed by his studio. The examination documented here is evidence that not every photograph with Choate’s studio imprint on it was taken by him, or taken in Carlisle. Most were, some weren’t. So, for me, if a photo doesn’t look “right” it’s worth it for me to dig around a bit and see what I can find. Particularly if it’s a photo of chief or other Native Americans in their own style of clothing, which seems to have been the most popular for Choate’s pirating.

This post originally contained another example, but in the course of writing it up I realized this appropriation was much more complicated than I had thought at first. You will have wait until for a future episode to learn about, to make it sound like a Sherlock Holmes story, The Strange Case of the Kiowa Baby.

As always, thanks for listening/reading and if you’re following along in real time, thanks for you patience with this long pause between episodes. I’ll do better from now on, I promise!

Resources:

Kate Theimer, “A Very Correct Idea of Our School”: A Photographic History of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, 2018. www.amazon.com/Very-Correct-Idea-Our-School/dp/1727272501

Richard L. Tritt, “John Nicholas Choate: A Cumberland County Photographer.” Cumberland County History. Vol. 13, No. 2, 77-90. gardnerlibrary.org/sites/default/files/vol13n2.pdf#page=10

Laura Turner, “John Nicholas Choate and the Production of Photography at the Carlisle Indian School,” Visualizing a Mission: Artifacts and Imagery of the Carlisle Indian School, 1879-1918. Dickinson College, 2004 chronicles.dickinson.edu/studentwork/indian/4_choate.htm